Juniper Publishers: I Have no Period, How can I Have Children: A Case of Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser Syndrome

JUNIPER PUBLISHERS- JOURNAL OF GYNECOLOGY AND WOMEN’S

HEALTH

Journal of Gynecology and Women’s Health-Juniper

Publishers

Authored by Shantalasha Onika Knowles*

Abstract

Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser Syndrome (MRKH) is not

frequently encountered and when cases are seen it is imperative that

the topic be revisited and shared with colleagues in order to grasp a

good understanding of its management. In this case report we present a

typical but delayed diagnosis in a 28 year old.

Introduction

Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndromeis a disorder

characterized by the congenital absence of the upper two thirds of the

vagina and an absent or rudimentary uterus in a phenotypical female

(46XX). It affects approximately 1 in 4000 - 5000 live female births [1].

It is known by other names that include congenital absence of the

uterus and the vagina, mullerian agenesis, mullerian aplasia or genital

renal ear syndrome [2]. The syndrome is named for the persons that described and documented their findings over a period from 1829 -1965 [3].

Most physicians will only see this condition once or twice in their

career. In this review we will describe the presentation,

classification, associated abnormalities, current genetic associations

and management options for improvement of sexual function in MRKH

syndrome.

Case Report

A 28 year old nulliparous patient presented to the

gynecology clinic with a complaint of amenorrhea. She noted that at the

age of 18 years old she got concerned when she did not have a period and

sought medical attention from a general practitioner. She recalls that

at that time she had an ultrasound that revealed the presence of an

“unusually small” uterus. It was unknown what additional testing was

requested, but due to financial constraints, she defaulted. Her new

concerns regarding the ability to conceive lead her to the gynecology

clinic. Attempts at coitus were unsuccessful with an inability to

achieve penile penetration. She never used contraception and was a

non-smoker and did not consume alcohol. She had no prior surgeries or

allergies. There was no cyclical abdominal or pelvic pain or changes

reflecting cyclical hormonal variations. She had normal breast

development and noted normal growth of pubic and axillary hair.

On examination, there was a young female of normal

stature (5ft) with a body mass index of 22.26kg/m2. Blood pressure and

pulse were normal. There were no obvious external anatomical

abnormalities and she had normal female axillary hair and pubic hair

distribution. Her breasts were symmetrical and normal with no nipple

discharge seen. The external genitalia was phenotypically female with an

annular hymen (clitoris and labia were normal). A small vaginal pouch

was palpated on digital exam (only the fifth digit could be introduced,

vaginal length was about 3cm). No female pelvic organs were palpated

bimanually. Speculum exam (done with a nasal speculum as a vaginal

speculum could not be inserted) revealed normal vaginal walls with a

blind-pouch, and no cervix was visualized. She was assessed as primary

amenorrhea with aims to fully elucidate the cause.

An abdominal, pelvic and renal ultrasound revealed

normal organs including two kidneys that were normal in size and

echopattern without hydronephrosis or calculi. The urinary bladder was

well distended, with no abnormalities. There was no uterus seen. A right

gonad was noted on the pelvic side wall that was suggestive of an ovary

measuring 2.5cm X 1.7cm X 2.6cm (no gonad was seen on the left).

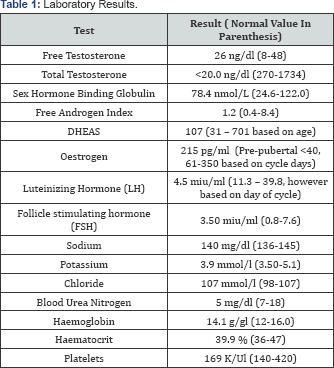

A hormonal profile, chromosomal analysis and a

magnetic resonance imaging was requested. The patient did not do the

MRI; however other test result were available (Table 1). The hormonal profile was normal and karyotype was 46 XX (Table 1).

The definitive diagnosis was mullerian agenesis. The

patient was thoroughly counseled and options regarding management were

discussed. She and her partner were comfortable with adoption, but noted

that use of assisted reproductive technology and surrogacy would remain

an option if desired. They wanted to be able to achieve coitus and the

patient wanted to avoid any surgical intervention and therefore

non-surgical creation of a neovagina was discussed which she agreed to.

Vaginal dilators are currently being used in this patient for the same.

Discussion

MRKH Syndrome can present similar to other conditions

that are also not commonly encountered. The differential diagnosis in

these patients include (but is not limited to); imperforate hymen,

transverse vaginal septum, androgen insensitivity syndrome (which is a

46XY disorder) and 17 alpha hydroxylase deficiency.

Most of these patients often present with primary amenorrhea but with developed secondary sexual characteristics [4-6].

Other presenting symptoms include the inability to have sexual

intercourse as in the case above or dyspareunia or infertility [4].

Classification

The syndrome is divided into the following three classes;

Typical MRKH (Type I)

This has isolated symmetric absence of the vagina or hypo plastic uterus.

Atypical MRKH(Type II)

This has asymmetric uterovaginal absence or

hypoplasia, absence or hypoplasia of one or both of the fallopian tubes

and malformation in the ovaries and/or the renal system.

MURCS (MUllerian agenesis, Renal Agenesis, Cervicothoracic Somite abnormalities)

This classification has the above with the addition

of a skeletal and or cardiac malformation, muscular weakness and renal

malformation. The typical classification is the most common type

followed by the atypical and MURCS.

Embryology

In females the mullerian ducts are present by the

sixth week of development and continued development, migration and

fusion during the twelfth week. Mullerian agenesis is caused by the

embryologic failure of the mullerian duct and sinovaginal bulbs, as a

result the vagina and uterus may not develop. The vagina may be absent

or shorter than normal. A remnant of the uterus or uterine horns may be

present [7].

Aetiology

Although cases of the syndrome are sporadic, there

are cases that have a genetic link. Research shows that there may be a

genetic component with deletions on chromosomes 1, 4, 8, 16, 17or 22 [8]. Duplication was also noted on chromosome X. Partial duplication of SHOX gene is found in some cases for MRKH [9]. Loss of function on the WNT4 gene has also been considered [10].

Anatomical Abnormalities

The predominant effect is in the genitourinary

system; however, the syndrome may affect additional systems besides the

genitourinary tract as some have alopecia arreata or hirsutism [11,12] Cardiac abnormalities have also been noted [13,14].

Other cases have been described with auditory, skeletal, hematologic

and endrocrine abnormalities such as diabetes and hyperprolactinemia [12,15-20]. The syndrome may also be associated with fibroids in the rudimentary uterus [21]. One case reports a possible association with metastatic papillary adenocarcinoma carcinoma [5].

Investigations

A hormonal assay (including but not limited to;

testosterone, oestrogen, FSH & LH and other tests to rule out

differentials should be requested, guided by clinical presentation.

Imaging studies are essential to assist with outlining the abnormalities

present in the genitourinary tract. Ultrasound and MRI are some

options. In most settings, ultrasound is available. However, it has its

limitations as it may not identify underdeveloped mullerian structures

and extra pelvic ovaries. MRI is the imaging of choice as it closely

correlates with surgical findings [22,23]. But it is more expensive than ultrasound and not readily accessible in all clinical settings.

Treatment and Management

The treatment of the syndrome involves a

multidisciplinary approach with emphasis on treating each aspect of the

syndrome. Counselling should be used to address the emotional and

psychological components of MRKH [24].

Nonsurgical and surgical options are available for the treatment of the physical aspect of the syndrome [25].

Non-functional uterine remnants may have to be resected

laparoscopically. A neovagina may be created to facilitate sexual

activity. A non surgical approach may be achieved by the Frank Procedure

or Ingram’s Method which entails use of dilators [26]. In one reported series 90% -95% of patients were able to achieve anatomic and functional success [27,28].

The surgical method is the creation of a neovagina via open, laparoscopic or robotic techniques [29,33]. Surgical methods include the older procedures such as McIndoe procedure and the Williams procedure [34]

using a split thickness skin graft and vulval flap respectively and new

laparoscopic techniques include the Vecchietti procedure, using single

peritoneal flap (SPF) and Davydov’s laparoscopic technique [35]. The tissues used may beautologo us or biologically engineered [36,37].

It is important that these patients be screened for human papilloma virus once they are sexually active [38]. Post-surgical complications may be encountered such as necrosis of the vagina or vault prolapse [39-41]. Patients that want to pursue childbearing will require the assistance of reproductive technology[42].

Summary

MRKH although rare, we are learning more about the syndrome, the causative molecular genetics, how to diagnose it and the subsequent management. The options exist for non surgical and surgical management of the syndrome. All options should be reviewed with the patient to facilitate function and improve patient overall satisfaction with the outcome of the treatment. In terms of fertility, options will depend on the initial organs that are present and their function, such as use of autologous oocytes via a surrogate carrier. However, with continued expansion in the reproductive and endocrine and infertility arena additional options may soon be readily at hand such as uterine transplant.

For more open

access journals in JuniperPublishers please click on: https://juniperpublishers.com/

For more articles on Gynecology and Women’s

Health please click on: https://juniperpublishers.com/jgwh/

Comments

Post a Comment