Juniper Publishers : A Review of Minimally Invasive gynaecologic surgery in Developing Nations

JUNIPER PUBLISHERS- JOURNAL OF GYNECOLOGY AND WOMEN’S HEALTH

Journal of Gynecology and Women’s Health-Juniper Publishers

Authored by Linus Chuang*

Abstract

Background and objectives: Endoscopic surgery may have added benefits in low-resource countries including improved recovery time,lower post-operative infection rates and decreased blood loss. These techniques are being used by gynecologists worldwide, but the extent is largely unknown. The aim of this review is to evaluate the laparoscopic gynecologic surgical capacity in low-resource countries and identify economic indicators that are associated with advanced skill.

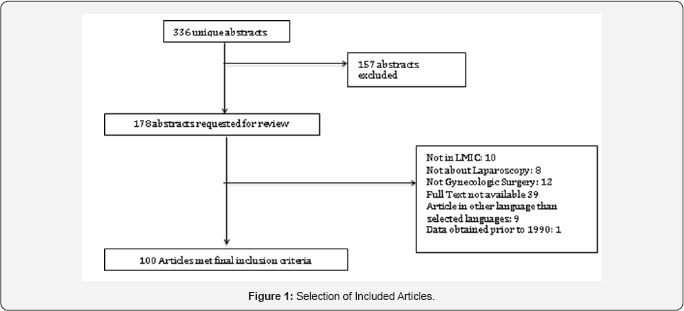

Methods: An online literature search was conducted; search terms included gynecologic, laparoscopy, minimally invasive, and low-resource countries. Of 336 abstracts identified, 100 articles were chosen in English and Spanish during between 1998-2015. Types of procedures, indications, and complication rates were grouped and compared according to World Bank Income Groups of Developing Nations: Low Income Country (LIC), Low-Middle Income Country (LMIC), or Upper-Middle Income Country (UMIC). Each country was categorized into Categories of complexity based on the highest level of skill required for reported procedures. The level of complexity was compared to World Bank Healthcare Development Indicators to identify correlates of advanced laparoscopic capacity.

Results: 14% of LIC report performing MIG procedures; twice as many LMIC and UMIC countries report such proficiency. LICs primarily perform diagnostic laparoscopies or adnexal surgery, with infertility being the most common indication. UMICs perform a variety of laparoscopic surgeries for benign and oncologic indications.

Conclusions: Minimally invasive surgery is widely adopted around the world. Advanced laparoscopic surgical procedures are increasingly performed in upper middle-income countries.

Keywords: Minimally invasive gynecologic Surgery; Low-resource settings

Introduction

There is growing momentum to increase access to surgical services in low-resource countries in order to reduce the global disease burden [1]. The benefits of investing in surgical infrastructure as a public health intervention are now evident. Compared with antiretroviral treatment or vaccinations, surgery can be equally as cost effective in averting Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) and has a strong impact on improving the productivity of a community [2].

As effort is put forth to increase surgical capacity globally, there must be a congruent aim towards safety and quality [3]. Minimally invasive surgery offers benefits such as reduced perioperative complications and improved recovery times that can be all the more beneficial to patients in low resource settings [4]. General surgery literature has identified many important benefits of minimally invasive techniques in low and middle- income countries. These included decreased infection rates post operatively in environments with suboptimal sanitation and reduced blood loss in the setting of limited blood-banking services [5].

Compared to the United States, thorough record keeping and reliable databases do not exist in most developing countries, leaving a paucity of comprehensive data regarding the promulgation of information about MIGS worldwide. Organizations such as American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists (AAGL) and the International Society of Gynecologic Endoscopy (ISGE) are helping to disseminate information and research regarding MIGS, but the current capacity of gynecologists to perform laparoscopy worldwide is largely unknown.

The objective of this review is to evaluate the overall capacity of Low and Middle Income Countries (LMICs) in performing MIGS procedures, by comparing procedure type, indication, and complications. Further, we aim to identify economic development indicators within health systems that may be associated with advanced laparoscopic capacity.

Materials and Method

Subjects

An online literature search was performed independently by the two first authors and also a team of two medical librarians using Google Scholar, African Journals Online and Pubmed using the MESH terms: gynecologic, laparoscopy or laparoscopic, minimally invasive, together with the individual names of all developing countries as classified under the World Bank Economic Classification system (Gross National Income (GNI) per Capita of less than $12,745 during fiscal year 2013). For instance, the following PUBMED search was performed for each developing nation: (((("Laparoscopy";[Mesh] OR "Hand-Assisted Laparoscopy";[Mesh]OR laparoscop*)) AND "Gynecology"[Mesh] OR gynecolog*)) AND ("Egypt" [Mesh] OR Egypt AND Journal Article [ptyp] AND Humans[Mesh] AND English [lang]) Filters: Journal Article, From 1990/01/01 to 2015/12/31, Humans, English, Core clinical journals.

Titles and abstracts were reviewed for articles describing a review of the development or current state of gynecologic surgery As there is no universally agreed upon definition of Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery, we included hysteroscopy, laparoscopy, robotic surgery, and pelvic floor procedures when referring to MIGS. Abstracts published between 1990 and 2015in English or Spanish were reviewed. Citations of retrieved articles were searched to identify additional relevant articles.

Study selection

Observational prospective studies, retrospective series, and case reports were included in the review. Articles describing a single indication for minimally invasive surgery or case series with laparoscopic treatment were also included. Literature reviews and editorials published by LMICs were excluded. In order to further characterize capacity and complexity of laparoscopic surgery in developing nations, abstracts presented at international conferences were included in the review if they included data about surgical capacity.

When applicable, the following information was extracted from each article: the overall incidence of gynecologic procedures performed via MIG techniques in the respective country, the types of procedures performed, the most common indications for surgery and complications encountered.

Data was grouped according to the Gross National Income (GNI) per Capita, and thus World Bank categorization of Low Income Country (LIC), Low-Middle Income Country (LMIC), or Upper-Middle Income Country (UMIC). The World Bank groups developing nations into the following three categories based on income: LICs have a GNI per capita (Fiscal Year 2013) of $1,045 or less; LMICs, $1,046-$4,125; UMICs,$4,126 to $12,745.

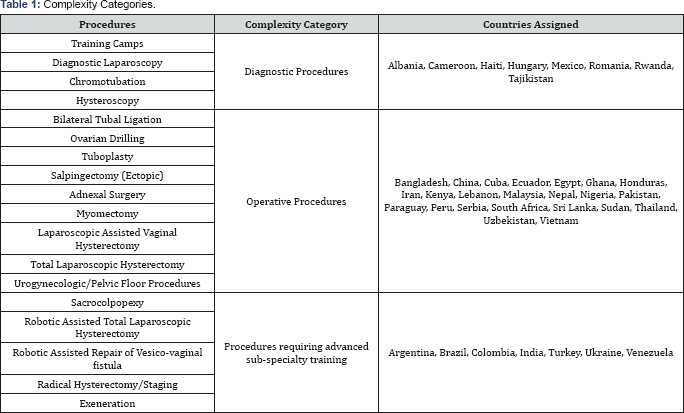

The complexity of various types of surgical procedures was ranked into three categories (Table 1): Diagnostic, Operative or Advanced Subspecialty training. Countries were assigned a Complexity Category based on the most difficult procedure reported in their literature. Countries only reporting basic diagnostic procedures with minimal operative performance such as hysteroscopy or diagnostic laparoscopy performed were assigned to the Diagnostic Category. Those publishing outcomes of operative procedures such as salpingo-oophorectomy or hysterectomy were placed in the Operative Category. Finally, countries demonstrating ability to execute procedures that require more technological skill and subspecialty training, such as a laparoscopic radical hysterectomy or lymphadenectomy, were assigned to the Advanced Category. These three categories were used to classify the types of procedures performed in LIC and LMIC as well as identify economic determinants that may confer advanced skill.

The three Complexity Categories were compared with economic income group and compared using a one-way ANOVA test. They were also compared against World Bank Healthcare Development indicators. These included: Total healthcare expenditure as a percent of GDP, healthcare expenditure per capita (in USD), percentage of public, out-of-pocket, and external resource health care expenditure, population, Income GINI Coefficient, hospital beds per 1000 people, and physicians per 1,000 people. By looking at these parameters, we aimed to identify factors that contributed to advanced laparoscopic skill. A one-tailed ANOVA test was used to compare the averages within each Complexity Category of each development indicator and identify a trend toward advanced surgical skill. Economic measures were obtained from the World Bank Database, with the most recent indicator from the last 10 years was used.

Results

One-hundred articles fit the inclusion criteria, taking place in 38 different countries. Table 2 shows the number of articles obtained for each country.

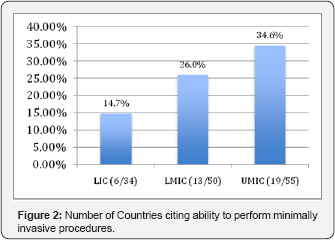

The rate of countries reporting laparoscopic capabilities increased proportionately according to each income group with only 6 out of 34 (14.71%) LICs reporting experience with MIG procedures, while 19 of 55 (34.55%) UMlCs described their experience in the literature (Figure 1). The incidence of MIGS procedures in relation to all gynecologic procedures was reported to be between 2.9-12% in the majority of LIC countries [6-8]. One outlying article from Nigeria stated that 2 3.7% of all gynecologic surgery was performed via laparoscopy [9].

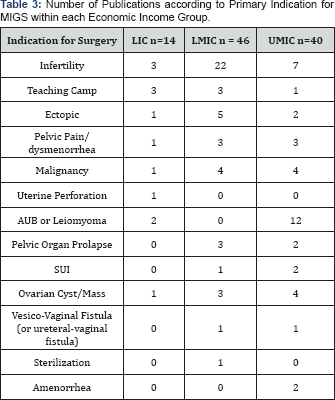

The indication most often cited for MIGS procedures in LIC and LMIC countries was a diagnostic evaluation of infertility (Table 3). Of all hysteroscopic and laparoscopic procedures performed in these two economic groups, 70.1% to 98.4 % of procedures are done in attempt to diagnose fertility issues [6,7,9]. In contrast, articles from UMIC report a wider range of indications for MIGS, varying from treatment of pelvic floor disorders [10] to extensive surgical debulking for gynecological malignancies [11,12].

The Diagnostic, Operative, and Advanced procedures varied between LIC, LMIC and UMIC. LIC only reported procedures in the Diagnostic or Operative Category, while UMlC had more varied distribution of countries reporting procedures in all three categories (Figure 2).

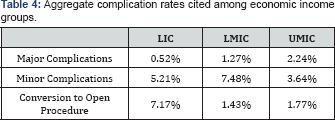

A total of 35 of the 100 articles reported adverse events that occurred during MIGS. The major and minor complication rates, as well as conversion rate to laparotomy, are shown in (Table 4). Major complications include bowel or bladder injury, vessel injury with subsequent hemorrhage, and vesicovaginal fistula. Minor complications include wound infection, separation or hematoma, as well as urinary tract infection, uterine perforation, post-operative lymphocele, vaginal cuff abscess, and ileus. Major complication rates are noted to be highest in UMIC. Yet, conversion rates from a minimally invasive procedure to laparotomy occurred less frequently in UMIC: 1.77% vs 7.17% of cases in LlC.

The World Bank Healthcare Development Indicators were trended in each Complexity Category (Table 5). Sixty percent (23/38) of all countries were assigned to the Operative category Five of the seven countries categorized in the Advanced Category were UMICs. Two healthcare development indicators demonstrated a trend with Complexity Categorization but did not reach statistical significance. The percentage of healthcare resources originating from outside the country, or "External Healthcare Resources," decreased from countries in the Diagnostic to countries in the Advanced category. (p+0.055). The percentage of healthcare expenditures originating from of external resources was the highest for countries in the diagnostic category at 13.7%, while only 0.37% of health expenditures were from external resources in the Advanced category

A trend was noted toward larger populations in the advanced category. The average population of countries in the Diagnostic group was 25 million, 110 million for the operative category, and 241 million in the advanced category. This difference was not statistically significant (p=;0.35). GNI Per Capita, Total Health Expenditure per capita, Public Health Expenditure, Out- of-pocket Health expenditures, Total Health Expenditure as a percentage of GDP, Income GINI coefficient, or hospital and physicians per capita did not proportionately increase with Complexity Category.

Discussion

There is growing consensus that surgical capacity building must become a priority of global health interventions [13,14]. Investing in basic surgical services and essential surgical care will be the next large focus of improving healthcare systems in low-resource settings [15]. As this is accomplished, infrastructure will be enhanced and so will the desire to perform minimally invasive procedures, as the benefits of such operations are clear. The advantages of MIGS are well published in UMIC. The same benefits: less wound infection, shorter hospital stay, and decreased blood loss have been demonstrated in various developing countries [16-18].

Our analysis demonstrates that endoscopic surgery can be performed across the globe, but the degree to which these operations are performed varies among income groups. The aim of this study was to identify associations and possible determinants of advanced laparoscopic capacity. The results were consistent with our hypothesis that increased economic development is associated with higher utilization and advanced MIGS skill.

The articles reviewed show that incidence of MIGS performance increases with economic income group. Only 14%; of LIC perform MIG procedures; LMIC and UMIC groups have twice as many countries reporting such proficiency. Higher economic status allows for the acquisition and maintenance of endoscopic equipment, which is a commonly cited barrier to uptake of laparoscopy in developing nations [5]. Fewer LICs and LMICs are able to overcome obstacles in raising capital for the initial purchase of equipment, and often do so by charging much higher prices for laparoscopy over open procedures [19]. A solution to this barrier is to develop a sustainable and continued relationship with an institution in a high-resource nation that is capable of providing training and equipment [20,21].

Indications for MIGS vary between economic groups as well. While LIC and LMIC report infertility and pelvic pain as the most common indications, there is a wider distribution of indications in UMIC. Applying MIGS to more complicated indications requires advanced equipment and training. The percentage of articles citing infertility as the primary indication for MIGS procedures may illuminate the uneven distribution of accessibility and difficulty to integrate the techniques into surgical systems at large. Diagnostic work-up of infertility in LIC and LMICs is often attainable only for patients with more resources to pay for elective procedures [22], thus highlighting a problem with accessibility to minimally invasive techniques. While MIGS procedures are available in low-resource settings, the indications to which they are applied often remain for patients who can afford the higher price of elective operations.

In comparing all reported complication rates of the reviewed literature to economic income group, major complication rates were greater in UMIC compared to LIC. This may be attributed to the types of surgeries performed in each group. While LIC and LMICs mostly describe basic diagnostic and operative laparoscopies, UMIC report complications associated with more technically advanced procedures [2 3]. All rates are comparable to complications published in high-income countries [24]. With time, the cultivation of laparoscopic skill will decrease complication rates [24,25].

The Development indicators did not reach significance in identifying trends among the three Complexity Categories. While External Healthcare resources had a non-significant trend with Complexity Category, this is likely related to a few outliers who receive a large proportion of their healthcare budget from outside donors. Complexity Category also trended with a country's total population. This relationship may possibly be due to the larger economies of scale in these countries. Greater purchasing power allows hospitals to have capital to invest in the cutting-edge technology such as the Da Vinci System [23,26]. The large markets of the "BRICS" Block (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) also have a larger pool of patients to seek out such procedures and make the initial investment more profitable.

This study is limited by several factors, the largest being publication bias. The amount and quality of data by country is highly variable, as no standardized reporting system exists in most nations globally with regards to MIGS. Many gynecologists in developing nations have adequate resources and training and offer MIGS to their patients but have not published their data. The literature search is also limited by the exclusion of articles in languages other than English and Spanish. As discussed, the review also does not talk about the distribution of laparoscopic surgery. A few countries have multiple studies from one author This likely indicates that there are a limited amount of providers or institutions providing such services, and thus is not reflective of accessibility at large. The small number of countries in this study limited statistical analysis of development indicators and surgical capacity. Greater differences may have been realized with more power [27,28].

Nonetheless, to our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive literature review of gynecologic minimally invasive surgery in developing nations. In the absence of reliable database used globally, it provides a basic scope of the current abilities of gynecologists in low and middle-income countries to offer patients minimal access surgery. The study most importantly shows that laparoscopic surgery can be utilized in low-income countries and that GNI per capita is not necessarily predictive of MIGs capacity. Further research is needed to identify ways of improving capacity in LIC and LMICs. Collaborative relationships with developed nations may play a role, whether through incountry training camps or opportunities abroad. Several articles report that the local surgeons who are performing laparoscopy received their training from physicians in high resource nations [20,21].

Moving forward, well-structured laparoscopic training programs for OB/GYN physicians in low-resource areas will be critical for expanding minimally invasive techniques into these parts of the world and improving patient outcomes [29,30]. The information obtained from this review may help minimally invasive gynecologists seek out appropriate partnerships in low- resource settings for mutually beneficial training experiences for trainees from both countries.

Data collection and research also need be prioritized in order to make minimally invasive techniques more accessible and safe for patients in LMICs. Anticipatory planning can help improve the cost-effectiveness of surgical care [31]. Such planning is only done by understanding the magnitude of problems within a particular infrastructure through data collection systems. As the WHO and others aim for a global surgical database for quality and safety, it will be important for the same measures be applied to laparoscopic and hysteroscopic operations. Data collection and research is imperative to the quality improvement process while developing nations advance their expertise with these techniques.

For more open access journals in JuniperPublishers please click on: https://juniperpublishers.com/

For more articles on Gynecology and Women’s Health please click on: https://juniperpublishers.com/jgwh/

To read more......Fulltext in Gynecology and Women’s Health in Juniper Publishers

https://juniperpublishers.business.site/

Comments

Post a Comment